A Camera That Fought for Justice

Sometimes a photograph doesn’t just capture a moment—it changes everything. That’s exactly what happened when Lewis Hine picked up his camera and aimed it not at landscapes or portraits of the rich, but at the dirt-covered, exhausted faces of American children forced into labor.

In the early 1900s, child labor wasn’t just common—it was the backbone of American industry. Kids as young as five worked brutal hours in mines, mills, factories, and farms. And while many adults turned a blind eye, one man dared to focus his lens on what others refused to see. Lewis Hine’s haunting images didn’t just document injustice—they dismantled it.

Meet Lewis Hine: The Man Behind the Mission

In 1908, Lewis Hine joined the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) as its official photographer. This wasn’t just a job—it was a calling. Hine wasn’t interested in taking pretty pictures. He wanted change. And he knew photographs could bypass bureaucracy and touch people in a way reports never could.

Armed with nothing but a camera, a notebook, and incredible courage, Hine traveled across the United States to expose the hidden cost of cheap labor—the stolen childhoods of working kids.

America’s Invisible Workers: Kids in the Line of Fire

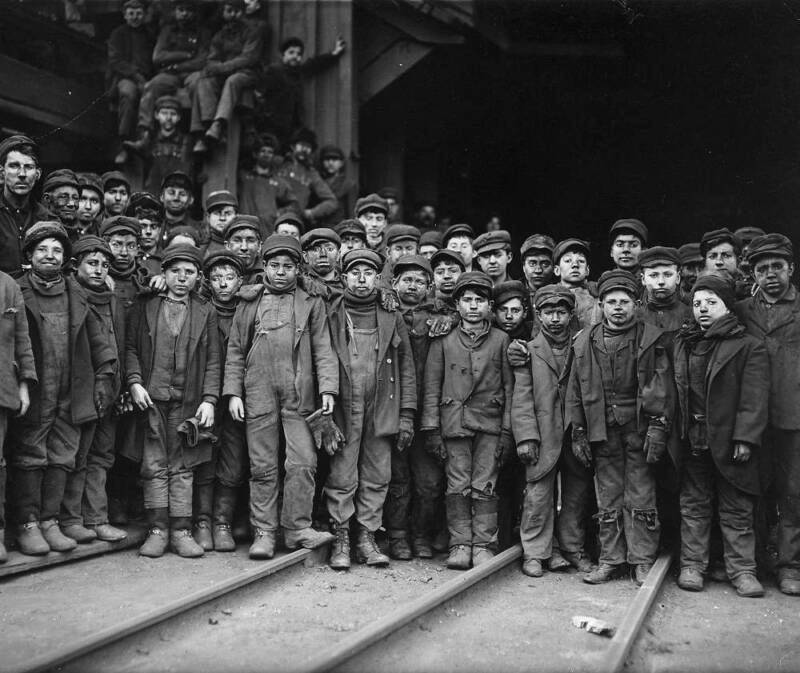

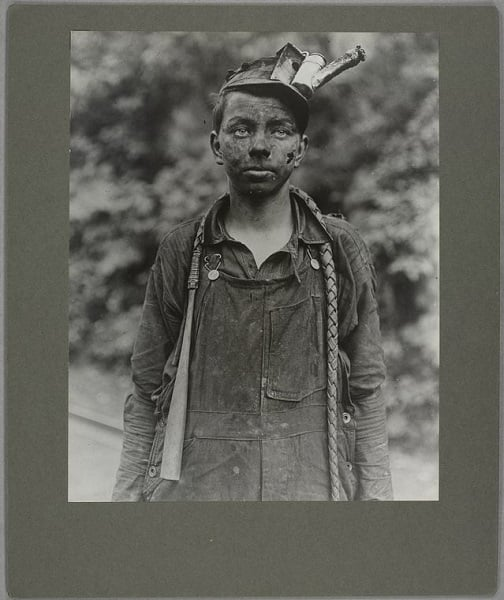

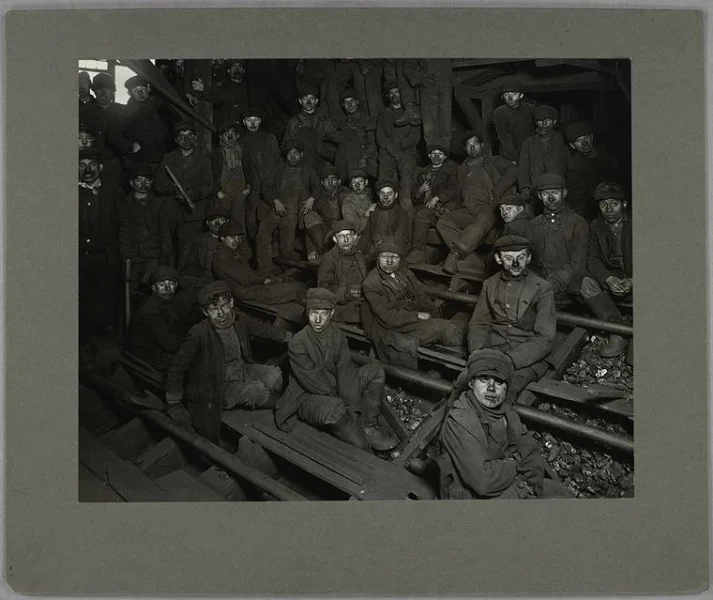

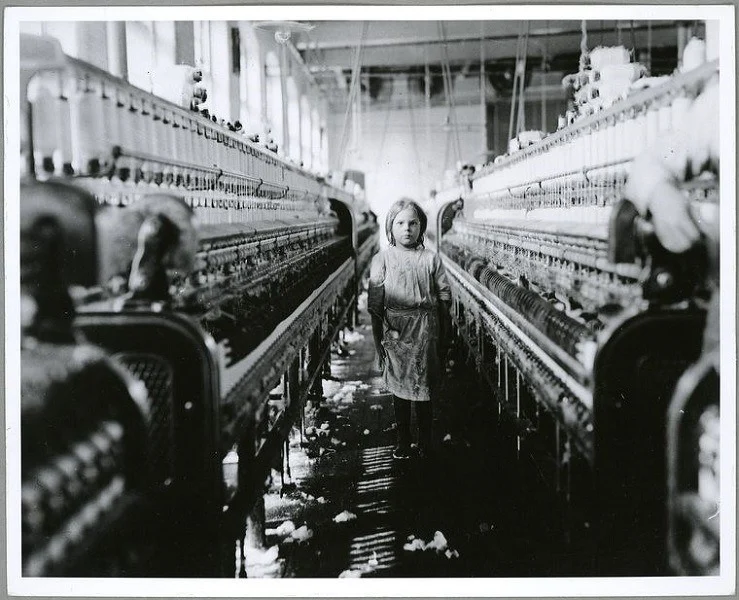

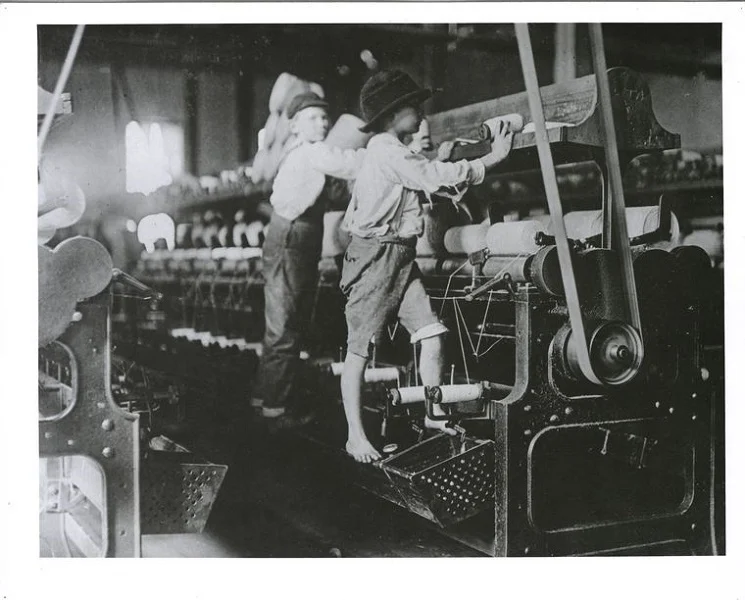

What Hine found was staggering. In textile mills across the South, young girls stood on tiptoe for 12-hour shifts, feeding spindles. In coal mines, boys known as “breaker boys” sat hunched for hours, sifting sharp coal from slate, their fingers bloodied. In canneries, children worked beside boiling pots, their backs bent and fingers blistered. There were no breaks, no protections, no childhoods.

These kids weren’t just helping out. They were essential to production lines, and they were paid a fraction of an adult wage—if they were paid at all.

And because profits came first, business owners fought tooth and nail to keep them working.

Video: These photos ended child labor in the US

How Hine Got the Shots They Didn’t Want You to See

Here’s the wild part: Hine wasn’t exactly welcome in these places. Factory owners and managers knew what he was doing—and they hated it. In fact, he was often banned from entering buildings. So what did he do? He got creative.

He disguised himself as a fire inspector. A Bible salesman. Even a postcard vendor. Anything to get inside and document the truth. He worked under constant threat—sometimes even facing physical violence.

And once inside, Hine worked fast. He took notes. Snapped photos. Got the names and ages of the children, and just as quickly, disappeared.

From Film to Reform: How His Photos Changed the Law

But taking the photos was only step one. Hine didn’t let his work gather dust in archives—he spread it far and wide. His haunting images were printed in pamphlets, magazines, exhibitions, and public lectures. They reached everyday Americans, educators, journalists, and—most importantly—lawmakers.

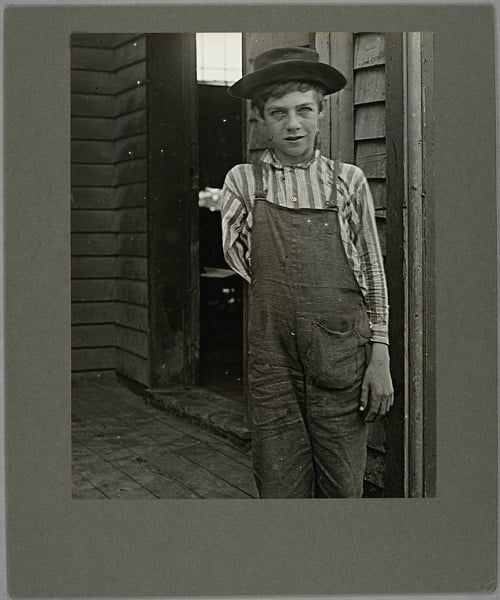

People couldn’t look away. A girl no older than nine staring dead-eyed at the camera with dirt on her cheeks and fatigue in her bones. A barefoot boy in overalls, holding tools larger than his arms. These weren’t abstract problems. These were children. And Hine made sure the country saw them.

In time, the wave of public outrage grew too loud to ignore. By the 1930s, after years of relentless advocacy by Hine and others, the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed—banning child labor and establishing laws that still protect young workers today.

Video: These photos once ended child labor in the US

23 Photographs That Forced America to Pay Attention

While Lewis Hine took thousands of photographs, 23 of them remain particularly unforgettable—each a gut punch, each a call to action:

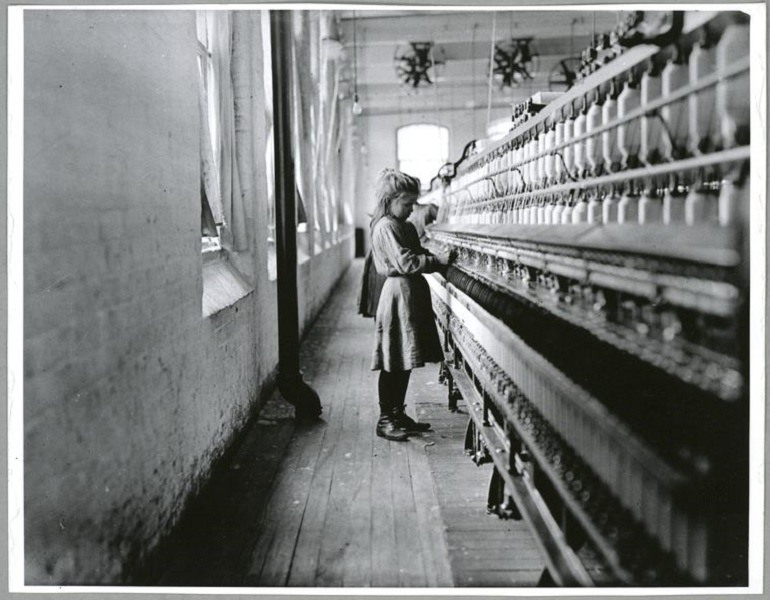

- A young cotton mill spinner, barely tall enough to reach her machine

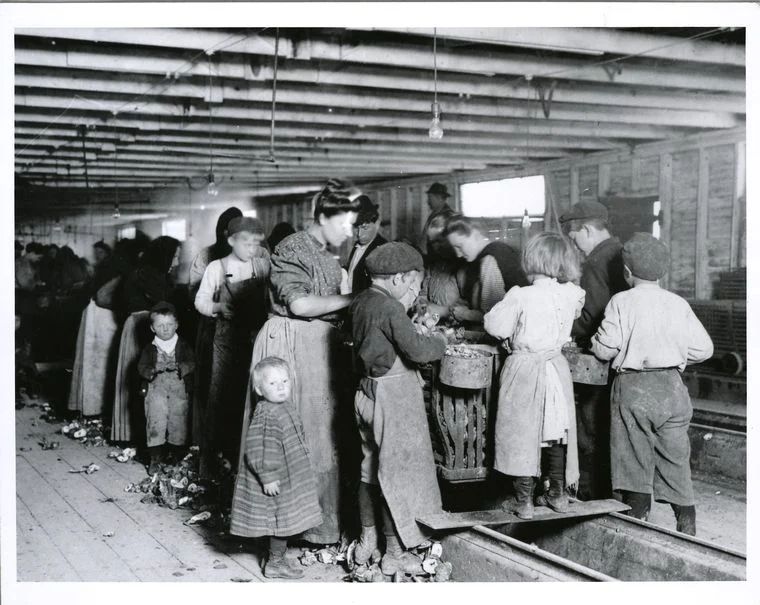

- A five-year-old oyster shucker, arms pruned from brine

- A newsboy asleep on the curb after midnight

- A group of coal-streaked breaker boys eating lunch with soot still on their hands

- A girl with bandaged fingers, her job requiring speed over safety

Each frame tells a full story in silence. A story of dreams denied, of exhaustion etched into young faces, and of a nation that had looked away for far too long—until now.

At the time of the 1990 U.S. Census, one in six children between the ages of five and ten participated in the workforce. In fact, at the time child labor made up 20 percent of the entire work force. Most were out of school and illiterate because their parents had no choice but to send them to work so that they could help support their families.

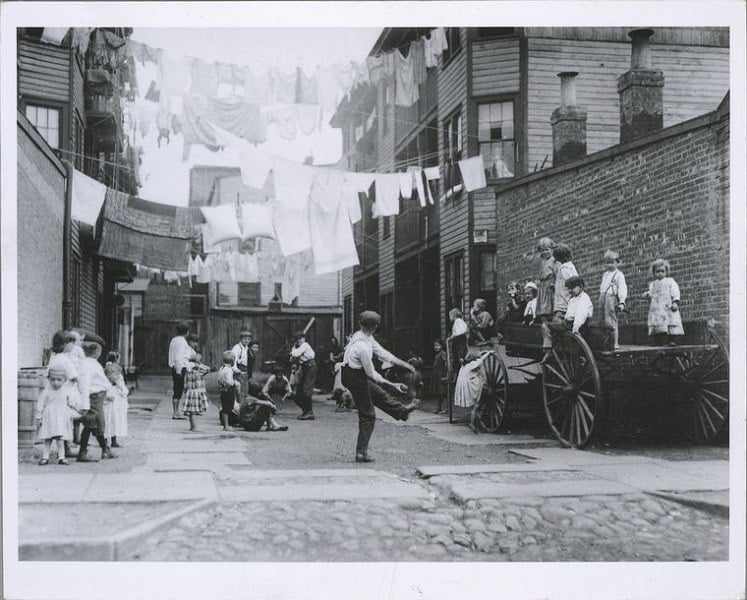

The Industrial Revolution had the effect of drawing more and more people moved to cities, where they would compete for low-wage, heavy-labor work.

Many families depended on their children for income, and with no labor unions or safety regulations in place to protect children in the work force, employers were free to exploit this new form of labor.

In 1900, around 1 million people were injured while working in a factory, many of them children. In fact, 50 percent of child labor conditions included hazardous work. Hands were mangled and fingers lost in the fast-moving machinery; exhausted kids who nodded off would sometimes fall into the machinery; and those confined to tight spaces died in explosions, cave-ins, and fires.

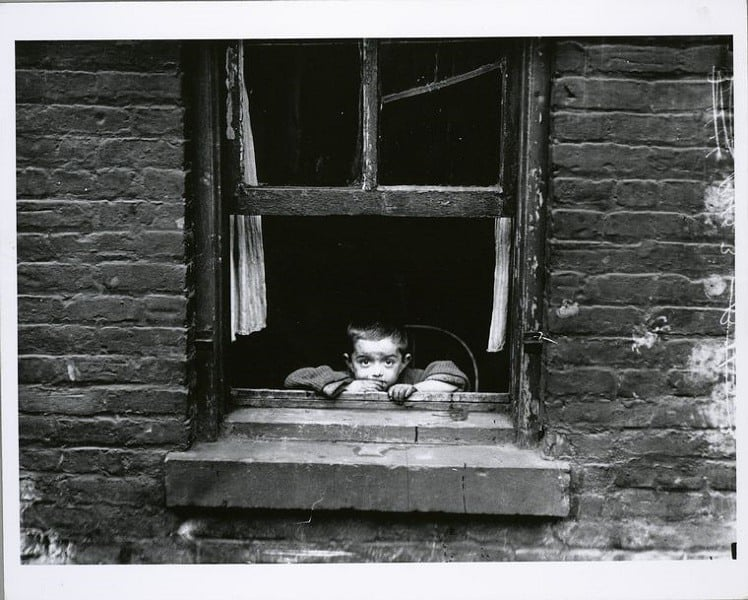

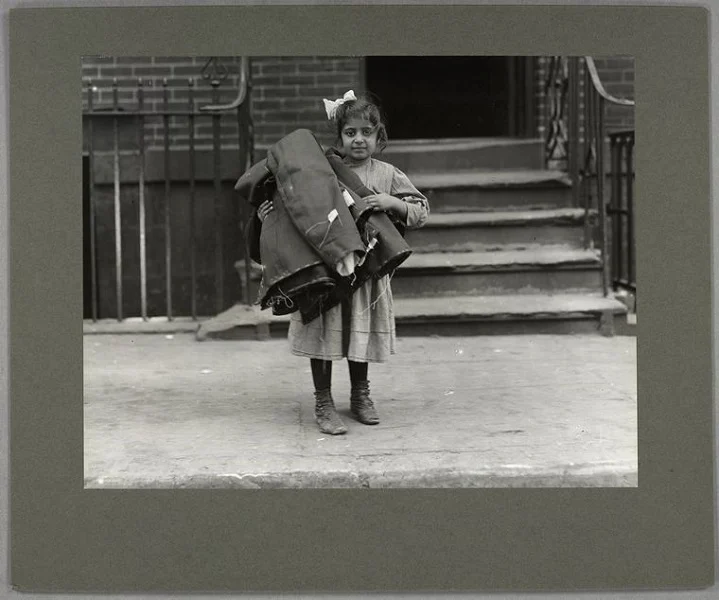

In New York, state laws prevented children younger than 14 from working in the factories. But in workshops set up in private homes, no such regulations existed. Thus, after their “work day” had ended, children often took home large bundles of unfinished garments from the factories so that they could finish them at home.

If New York City child laborers were lucky, they worked in “new law” tenements, which operated in full compliance with lighting and ventilation laws. More often, though, these children and their families — usually immigrants — lived in dilapidated, over-crowded and barely-livable tenements.

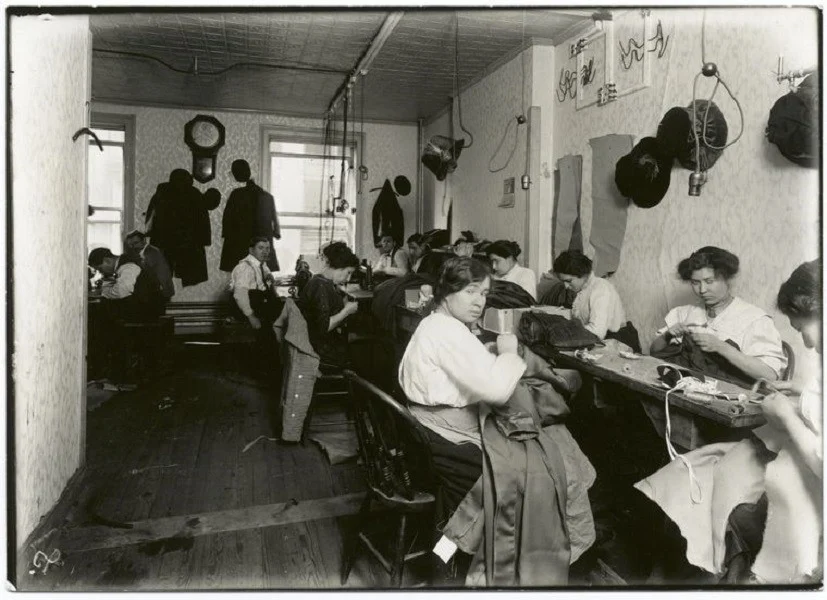

In some of Lower Manhattan’s tenement houses, children made artificial flowers in makeshift factories. Some families made up to $20 per week, but that meant that children worked until 8 p.m., making as many as 1,700 flowers per day, and then attended school the next day.

In addition to artificial flower making and garment work, women and children shelled nuts in their at-home workspaces, picking up the slack when the male breadwinner in the family was out of work.

Often, parents kept their children at home and forced them to do garment work, like sewing buttons on trousers (which sometimes paid as little as six cents a piece).

Forcing very young children to stay home from school violated the law, but once a child passed the age of 14, truant officers could not enforce compulsory education laws.

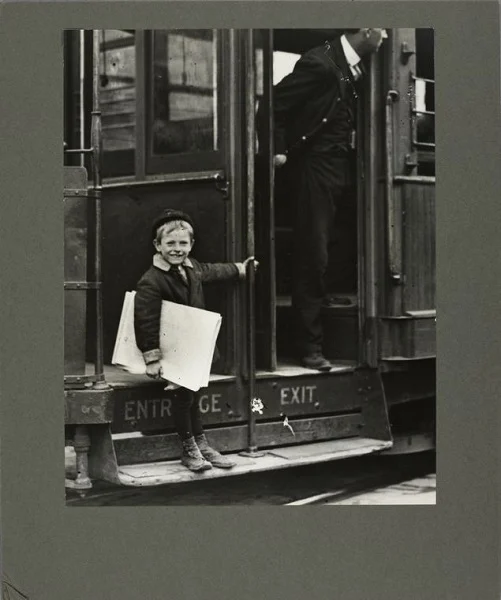

In the late 1800s, as many as 10,000 homeless boys lived in the streets of New York City, sleeping beneath the stairways of newspaper offices. Once they got their hands on the day’s papers, they harassed pedestrians for money, still usually only making 30 cents per day.

In 1899, however, news boys went on strike. They refused to handle the newspapers of Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst until the companies provided better compensation for the child labor force responsible for widely circulating their publications.

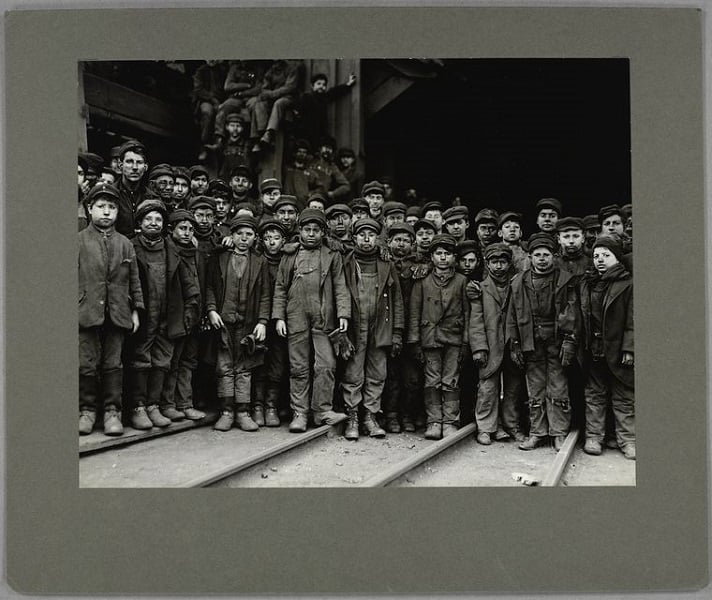

“Breaker-boys” like these children worked in the coal mines of Pennsylvania, where they separated coal from slate by hand. They usually worked ten hours per day, six days a week.

Asthma and black lung were common among breaker-boys, and many lost limbs after being caught in machinery, or were crushed to death by mounds of coal or under the conveyor belts they worked near.

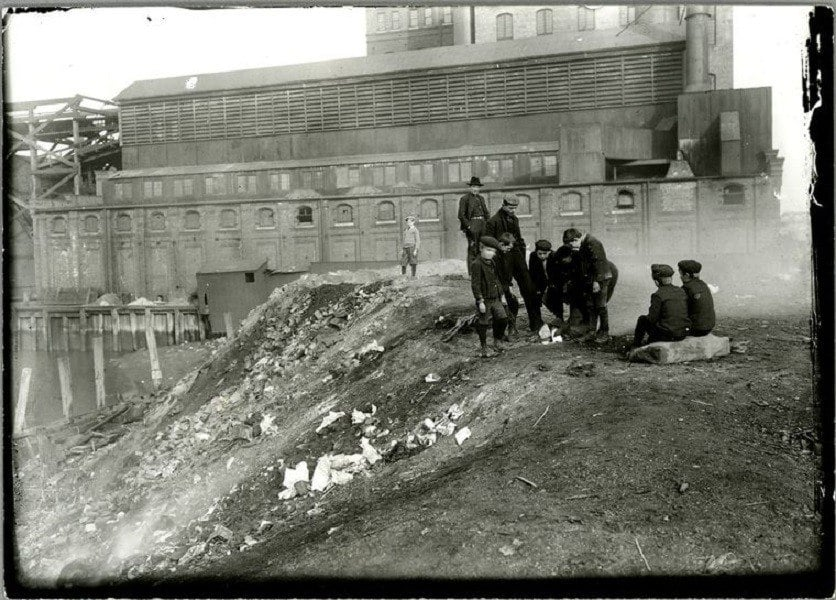

Children play a card game outside a factory building.

Public outcry against children working in these conditions helped create a Pennsylvania law that banned anyone under the age of 12 from working in the state as a coal breaker. But the law was poorly enforced: Families sometimes forged birth certificates so that their children could continue to help support the family, and because child labor was cheap and profitable, employers often forged these documents themselves.

Eventually, new technology, like mechanical and water separators, made breaker boys obsolete. Mandatory education laws and stricter enforcement of child labor laws, by and large brought about by the photographs of Lewis Hine, helped end the practice by 1920.

Elsewhere, children working in cotton mills, like this one in North Carolina, were often orphans. The mills employed these children in exchange for shelter, food, and water.

In the mills, children as young as five and six years old worked ten-hour days six days a week without breaks. What’s more, scraps of cotton filled the air, causing frequent cases of lung disease.

Children in mills also worked as doffers, replacing the spools in the spinning machine (and risking falling into the machinery) or as spinners. For their trouble, child laborers in the mills earned 40 cents per day.

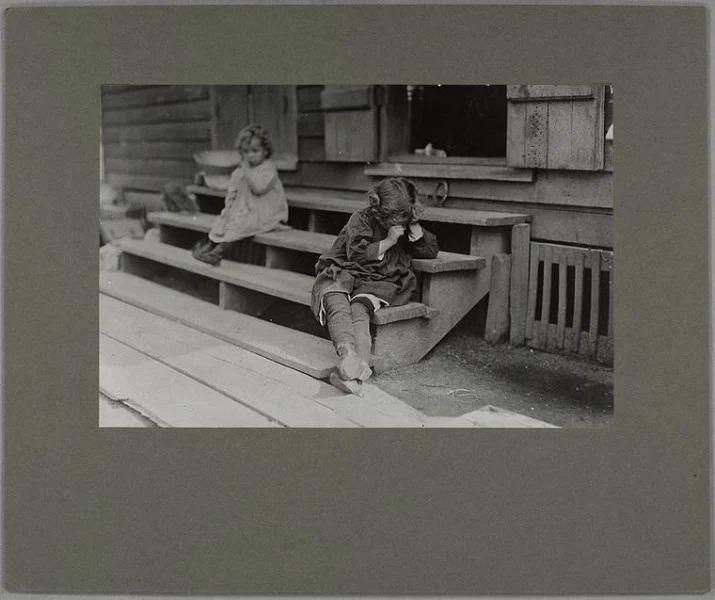

A young girl rests after a long work day.

During this period, factories were not heated or air-conditioned, and lacked sufficient ventilation and lighting. Pay was no better: Girls working in 1850s garment factories, for instance, made just a little more than 100 dollars per year.

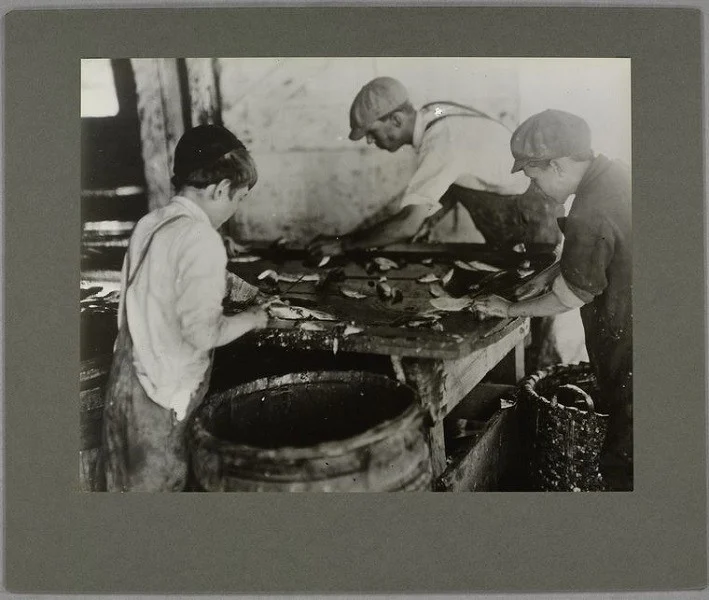

In Maine’s sardine canneries, small children, called “cutters,” were given knives to cut off the heads and tails of the fish. Because employers incentivized dangerously quick work, and because the fish could be quite slippery, copious injuries ensued.

In the South, children worked shifts as oyster shuckers in canneries before and after attending school. Employees at the canneries usually worked 14-hour days, and lived in special camps set up to house the factory’s entire work force.

Mothers often brought their children to factories because they lacked childcare options. Even though children did not receive a permit to work in the canneries until 14, the younger ones still helped shuck, but would sometimes have to hide if an investigator came to inspect factory conditions.

Though the National Child Labor Committee was established in 1904, child laborers would have to wait more than 30 years until comprehensive restrictions and laws were put into place — partly with the help of Hine’s photos.

The Fair Labor Standards Act, passed in 1938, finally fixed the minimum age of employment at 16 (18 for more dangerous work) and restricted the number of hours that children were allowed to work — effectively creating what many take for granted today: childhood.

The Legacy of Lewis Hine Lives On

What makes Hine’s work so powerful, even a century later, is how deeply human it feels. He didn’t photograph statistics. He captured souls. Kids who should’ve been in school or at play were instead pushing the wheels of industry. And through his lens, he gave them dignity, visibility, and ultimately, justice.

Today, his work is housed in libraries, museums, and classrooms, not just as history—but as a warning. Because child labor still exists in parts of the world. And his photos remain a reminder of what happens when profit trumps people.

Conclusion

Lewis Hine didn’t just take photos. He took a stand. In a time when children’s pain was swept under the rug, he exposed it to the world. He believed a picture could spark outrage—and he was right.

Because of him, laws changed. Because of him, children were freed from factories. And because of him, we remember that sometimes, the most powerful weapon for justice is simply a lens focused on the truth.